STAGE AND FILM

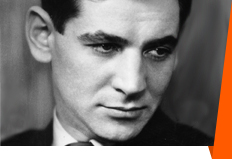

- Leonard Bernstein

- Stage & Film

- Concert Music

- The Conductor

- The Educator

- Bernstein’s New York

- Bernstein and Faith

- The Social Activist

- Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic

- Bernstein Memory Bank

- Bernstein Timeline

Hollywood Glitter and the

Great White Way

“That is what I feel I write best, what I ought to do and what I most enjoy.” These were Leonard Bernstein’s thoughts on composing for the theater in 1953. Only nine years previous, just after he finished composing his first musical, Bernstein sounded far less convinced: “On the Town represents a six-month period out of my life. I’m primarily a conductor. It’s not as easy to grow as a conductor when you’re diverting your energies in so many other directions.” Bernstein’s ambivalence about how to direct his musical energy never entirely vanished. At age 38 he joked, “Someday, preferably soon, I simply must decide what I am going to be when I grow up.”

Whatever doubts Bernstein had about the legitimacy of composing for Broadway, he seems, in retrospect, to have been ideally suited for the task. Not only did he thrive in collaborative settings, but he also had a gift for writing music that fused high and low idioms and pulsed with kinetic rhythms that were perfect for dancing. Perhaps most importantly, his ability to render drama in musical forms was superb.

Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

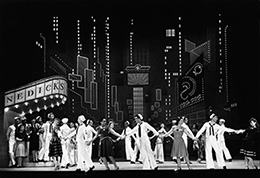

On the Town came out in 1944, just one year after Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma. Where Oklahoma was wholesome and pastoral, On the Town was racy and urban. With a mixed-race cast, candid sexual humor, and substantive female characters, On the Town managed to be popular and provocative at once.

Bernstein forewent any serious composing for the theater for eight years to focus on conducting. His next major work was the short opera Trouble in Tahiti, a domestic drama set in suburban America. Though the work contained clear elements of social critique, some close to Bernstein also saw the opera as a cathartic depiction of his parents’ own troubled marriage.

While deciding what to be when he grew up, Bernstein also composed the score for Elia Kazan’s film On the Waterfront, starring Marlon Brando. Bernstein was used to collaboration, but this project required an unprecedented level of self-effacement.

“I was swept by my enthusiasm into accepting the commission,” he wrote, “although I had hitherto resisted all such offers on the grounds that it is a musically unsatisfactory experience for a composer to write a score whose chief merit ought to be its unobtrusiveness.” Despite this constraint, Bernstein was able to fashion a score of inherent musical interest that also served the dramatic needs of the film.

Bernstein turned back to Broadway in 1956 with Candide, an operetta based on Voltaire’s classic 18th-century satire. Though the highbrow humor may have limited the show’s success, Bernstein’s overture has entered the standard repertoire, and recent revivals of the show have enjoyed great popularity.

Bernstein’s next Broadway project is often considered not only the peak of his writing for the stage, but one of the greatest American musicals ever written. A loose adaptation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, West Side Story placed the story of doomed love in a modern New York of ethnic hatred and violence. Jerome Robbins, who choreographed the show, described the extraordinary chemistry of the musical’s collaborators, with “each taking hold of something and saying, ‘Hey, I think I can do that,’ or saying, ‘No, don’t write it as music, we can do it better in book’—or ‘don’t do it in song, I can do it better in dance.’” The result was that rare thing—a musical that satisfies on all levels.

© 2001–2008 Carnegie Hall Corporation

- Home

- |

- Multimedia

- |

- Press

- |

- Partners

- |

- Supporters