THE CONDUCTOR

- Leonard Bernstein

- Stage & Film

- Concert Music

- The Conductor

- The Educator

- Bernstein’s New York

- Bernstein and Faith

- The Social Activist

- Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic

- Bernstein Memory Bank

- Bernstein Timeline

The Need to Lead

There are these ecstatic poses in hundreds of photographs, inspired music making on dozens of recordings—but Leonard Bernstein didn’t initially aspire to be a conductor. He began as a pianist and a composer at Harvard, and then met conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos. “Mitropoulos had put the idea in my head that I must be a conductor,” Bernstein later recalled. “I never had this ambition or vision of myself—it seemed far too remote and glamorous a thing.”

He saw just how glamorous conducting could be one day in 1943, when the sudden illness of conductor Bruno Walter forced the 25-year-old Bernstein to lead the New York Philharmonic on a moment’s notice. The concert, which included challenging works by Schumann and Wagner, was wildly successful. Bernstein became a musical celebrity overnight.

Glamour continued to cling to Bernstein’s conducting persona. The composer John Adams recalls thinking of Bernstein, “This guy looks more like James Dean than Toscanini.”

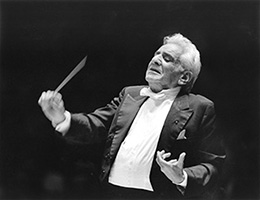

Leonard Bernstein conducting. Steve J. Sherman. Courtesy of Carnegie Hall Archives.

But beneath his charm and good looks was a profoundly gifted and serious musician whose work redefined the potential of an American conductor. Led by elderly foreign luminaries for many years, the New York Philharmonic made the historic decision to appoint Bernstein—a homegrown and relatively young American—as music director. Bernstein was also among the first conductors to promote and explore American concert music. He was an ardent champion of American concert music, introducing works by Charles Ives, Lukas Foss, Ned Rorem, Aaron Copland, William Schuman, and David Diamond.

Bernstein’s conducting was also deeply connected to his immersion in the music of Gustav Mahler, whose current centrality to the orchestral repertoire is largely a product of Bernstein’s efforts. As a fellow Jew torn between conducting and composing, Bernstein felt a personal (as well as musical) affinity with Mahler. He conducted Mahler’s Second Symphony, “The Resurrection,” in honor of John F. Kennedy just two days after his assassination; he also chose to conduct the Adagietto of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony at St. Patrick’s Cathedral to commemorate the death of Robert Kennedy.

The famous flamboyance and exuberance that characterized Bernstein’s physical style on the podium provoked criticism from some, but the musicians he conducted generally felt that playing under Bernstein was an emotionally transcendent experience.

“You couldn’t just play a solo according to the legal letter of the notes,” recalled John Cerminaro, who played in the Philharmonic’s horn section for many years, “he wanted you to give; he wanted you to sweat with him.” Bernstein himself conceived of his relationship with an orchestra as physical, even carnal.

“There is a kind of closeness that can develop with the members of an orchestra in which you and a body are breathing together, lifting and sinking together,” Bernstein said. “Am I making this sound to lurid? Too sexual? It is sort of sexual, but it’s with 100 people.”

© 2001–2008 Carnegie Hall Corporation

- Home

- |

- Multimedia

- |

- Press

- |

- Partners

- |

- Supporters